Next Installment from Caroline Recker, farm friends and adventures.

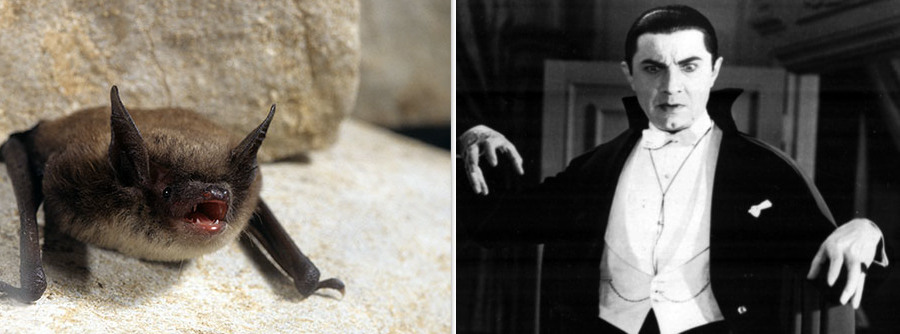

The common vampire, pictured here in both bat and humanoid forms.

Did you know July is Rabies Awareness Month? If you said yes to that question, you’re a liar, because it’s actually in May (or March, but only in the Philippines) and there is also a World Rabies Day celebration event on September 28th.

But why am I talking about rabies, you ask? Well, the farm school recently hosted a local bat for an overnight workshop of terror. By which I mean it was terrified. And so was I.

Venture back with me, reader. The day was June 28th. I had been staying at Quillisascut for 2 weeks. The sun set at 8:57 PM. Dracula Daily fans had not heard from Jonathan Harker in 3 days. My hosts were dining with their friends that evening and I was lying in bed reading, well, not Dracula, but The Valley of Fear by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It was finally dark outside, and as a creature of night, I was at ease. Alone.

An odd fluttering sound disrupted my requiescence. It was like the drumming of impatient fingers on taut leather, and it was followed by a thudding, scrabbling clamor. I peered at the ceiling. The light switch was unhappily far away but I scampered across the room and turned on the lights. I have always admired the trusses that stretch across the upstairs bedrooms, but now I squinted at them in suspicion. Could they be harboring the unseen hopefully-not-a creature? The space above my head seemed clear. I opened the door and aimed my phone’s flashlight around the upstairs landing, then tiptoed out of my room. I heard an angry flapping and hoped to find a nocturnal bird.

No luck. Flitting around in a crazed, apparently characteristic U-shaped pattern, was a bat. Seeing that it had chosen the neighboring bedroom as the site of its wretched winging, I skittered farther away to watch.

Before I continue, I must describe the architecture of my current housing. Each of the second floor rooms has a door to the outside; my room and the bat’s room both lead to a deck which can only be reached from the ground via a ladder. The remaining rooms open onto another deck which has a small ramp leading to the ground. I have already mentioned the roost-friendly beams. But above the door of each bedroom, there is also a sizeable gap. Rick tells me these are called transoms. They allow for airflow through the rooms and contribute to a communal feel. They are also bat highways.

This dynamic photo is illustrative of both the pro-bat setup and my panicked state that evening.

Alone on the farm and in need of moral support, I called my partner, Dustin. He began researching bat evacuation techniques while I watched the seemingly endless loop of bat panic. According to the internet, a bat will seek dark spaces and shun well-lit ones.

“At least it’s staying in one spot,” I said, like a fool, before the bat pelted out of the dark room towards my own brightly lit sanctuary across the way. I yelled an expletive which I will not repeat now and slammed the door.

A stunning visual aid if you’re confused.

Fortunately, I had shut myself in a room which provided easier access to the ground. Unfortunately, I had forgotten my shoes. I picked my way through some overgrown weeds to the gravel (ouch) driveway and assured Dustin that I was not dead. A whimper caught my attention: Lucy the Anatolian Shepard had heard the commotion. Lucy guards the livestock and also me, it would seem, because she bounded up to meet me, marking the second time in 3 minutes that a frenzied creature was shooting towards me at top speed. I renewed the reassurances that I was not dead. But would I survive the night?

Dustin and I refined the light-exclusion strategy, deciding that I should disregard the recent disproof of the bats-won’t-go-to-light theory and light up all the rooms but one, in which I would also open the door. I had lost track of the bat when I fled, but I gambled that it had chosen the dark room adjacent to my former sanctuary and resolved to open that door. This had the added benefit of being easily reached from outside.

Chief on my mind was rabies, that hydrophobic disease which, like quicksand, has a mythic notoriety that far outstrips its real-world incidence. The issue, of course, is that rabies is virtually 100% fatal. Bat fangs are so tiny and sharp that bites may not be felt. Couple these phantom bites with definitely-going-to-kill you disease and it’s no wonder the CDC advises any person who so much as sleeps in a room with a bat to seek medical attention.

I slipped into the front door of the farm school and immediately turned on the lights, surveying the ceiling. The once rustic rafters of the living room now seemed menacing. But I had to be brave! I put on my long-sleeved gardening shirt and gardening gloves and gardening hat. Regrettably, I was not going to garden. I was preparing to tangle with a bat. I recalled the enormous quantities of garlic scapes in the walk-in, but I couldn’t be sure of their potency in the face of an undead threat. The false security might be unwise. I marched back outside, grabbing a jug of water to prop open the chosen door. I felt foolish envisioning my hosts returning to find me in full garden regalia in the dying light. Too soon, I reached my destination and steeled myself to go back into the depths.

3 of the approximately 2,460 garlic scapes in the walk-in

“Good-bye, Dustin, if I fail; good-bye, my faithful friend and second doggy; good-bye, all, and last of all Dustin!” is what I would have said, if I were Brahm Stoker. Whatever I said was not so eloquent as to be worth remembering, followed (presumably) by a deep breath and a tight grip on the door handle.

A small bit of anti-climax: there are 2 doors in each room. The first is a screen door for ventilation, but the second is my actual object. The curtain was drawn across the window so I could not see into the room. I did not know what awaited me. But I pushed in the door and—

–hit the box fan that someone had set in front of it, thus preventing me from actually opening the door. Merde. I abandoned the water jug outside the door and returned to my sanctuary. The logistics of opening my planned door were daunting: I would have to dive into the room, scoot the fan aside, open the curtain, sprint away, turn on the remaining lights, head outdoors, open the correct door (finally) and prop it open with the jug. I have often wished I was a Slayer, but I see now that I probably couldn’t handle it.

My poor long-suffering partner attended the whole maneuver, listening to my little shouts of fear and reassuring me that my instinct to keep low to the ground was likely correct. (Later research suggested that bats are also proficient crawlers and it is best to avoid the floor. I don’t know what options remain for those of us who cannot levitate.) I thought perhaps I heard my hosts return but there was no time to waste feeling embarrassed. And finally, finally, my bat tunnel complete, I fled downstairs to wait for bat liberation.

Lucy: 12/10 good dog

“Caroline?” Either the bat had learned the power of human speech (all vampires speak common, so this wouldn’t be surprising) or the voice calling me was Rick. I felt very sheepish ascending the stairs.

Rick was wearing a headlamp and a confused expression. I explained the whole bat thing, and together we examined the bat-free ceiling and decided that it had probably fled while I was downstairs. Rick pointed out the clock hanging on the wall near my sanctuary—the hour, minute, and second hands had tumbled to the bottom of the clock and were piled inside the plastic casing. Could this have been the bat? Could it have happened when I gently and calmly closed the door earlier?

I had to stifle a laugh. Rick came home to his house entirely lit up, seemingly empty, with the sort of harmless, aberrant property damage one would normally expect from a vengeful ghost in the first 30 minutes of a horror movie. But we agreed, the house was haunted no more: the bat had moved on. Rick went home and I went to bed, feeling a bit foolish but relieved.

It took a long time for me to unwind and fall asleep. But with every passing minute, I felt more assured that the brief nightmare was over. I peered out of my room with a flashlight and brushed my teeth. I peered out of the bathroom with a flashlight and went back to my room. I turned off the overhead lights and did my final necessaries: soft scrunchie in my hair, lotion for my frequently-washed hands, eye mask to shield me from the 5 AM sunrise.

That’s when my leathery friend soared from behind the truss and out through the transom. It had lingered in its new hibernaculum ten feet from my head and waited for my greatest moment of unreadiness to reveal itself.

It was too late for another door-opening light-switching rigamarole. I filled my sleeping bag with my possessions and carried it over my shoulder like a bindlestiff, down the stairs to the single transom-less bedroom which would allow me to shut out the winged blight and shield me from disease. There I spent an uneasy night, fearing to emerge from my place of hiding lest the beast swoop down upon me and plant its fangs in my unsuspecting neck.

Image © Ondrej Prosicky/Shutterstock.com

30 June, morning— “No man knows till he has suffered from the night how sweet and how dear to his heart and eye the morning can be.” Jonathan Harker knows, as do I, that sunlight means safety. While Jonathan will find himself locked in the castle once more on June 30th, I was not myself locked in my room. Daylight shone fierce and glad upon me, dispelling my fears of bats and ‘bies.

Despite my caution the following evening, and another night spent downstairs, I never saw the bat again. I’m not sure what happened to the little fella. I hope it’s doing well, and I hope it made its home somewhere else. Maybe all was lost when I took my eyes off its path. Maybe not. By the third night, I felt safe to return to my room. As darkness fell outside, I climbed into my coffin and snuggled my shoulders beneath the fresh earth, ready for a bat-free rest.

Your friend,

Dracula

P.S. Okay. I know the bat wasn’t a vampire. It came into the house without an invitation, which is decidedly counter to the lore. And yet… I’ve been craving flies…